Historical Art and Architecture is one of the most dynamic sources of history. There is not just history ‘of ‘ Art and Architecture; but there is substantial history that can be inferred ‘from‘ art and architecture. It allows us to speculate about the ideas, politics, philosophies, knowledge systems of various periods in history. It also allows us to interrogate about their utility, nature and choice of material for construction, whether they were manifested as ‘art’, the way we understand it today; the multidimensional functions it performed when it was built and the functions it took up later ! The Lion capital of Sarnath, was sanctioned by Emperor Ashoka for various reasons; but it still holds relevance in the Republic of India which came up almost two millennia later. The dynamism of ‘art and architecture’ as sources of history lies in the fact that it doesn’t speak for itself and has to be interpreted; and the results of such discourses will always have so much to tell us; perhaps way more than we as students of history are capable of asking. Today if one travels across south India, he/she cannot miss observing temples; big or small, irrespective of their antiquity; let’s say the ones with brightly painted and towering gopuras and vimanas. Ever wondered when this particular style got standardized ? The Dravidian style of architecture was an innovation of Pallavas and Chalukyas; the process and stages through which it was reached, has a complicated narrative of its own.

The Pallavas were an early medieval dynasty who ruled major portions of the far south and contended with their neighbors, the Chalukyas who ruled major portions of the Deccan. The political history, achievements and dynamics as recovered from inscriptions, literary texts and travel accounts is just one avenue to understand them . The Architectural edifices left by them take us to a completely different world characterized by dynamism, innovation (technical, spiritual and political) and artistic finesse.

Building activity of the Pallavas began under Mahendravarman-1. This can be claimed only with due acknowledgement of the fact that Mahendravarman was the pioneer, when it came to, engaging in building activity with imperishable materials like stone, unlike the previously used wood, timber etc. An inscription issued by the king himself found in Mandagapattu cave temple (also called Lakshitayana ) throws some light on this aspect.

The poetic Sanskrit inscription written in Grantha script can be translated as follows:

“The temple dedicated to Brahma, Siva and Vishnu was excavated by Vichitrachitta without using brick, timber, metal and mortar”.

Temples are chronologically analyzed by art historians based on stylistic conventions and the presence of inscriptions; though the latter is not always reliable as there are evidences of inscriptions being inscribed at a much later date. Stylistically and paleographically, the Mandagapattu cave temple can be ascribed to Mahendravarman-1.

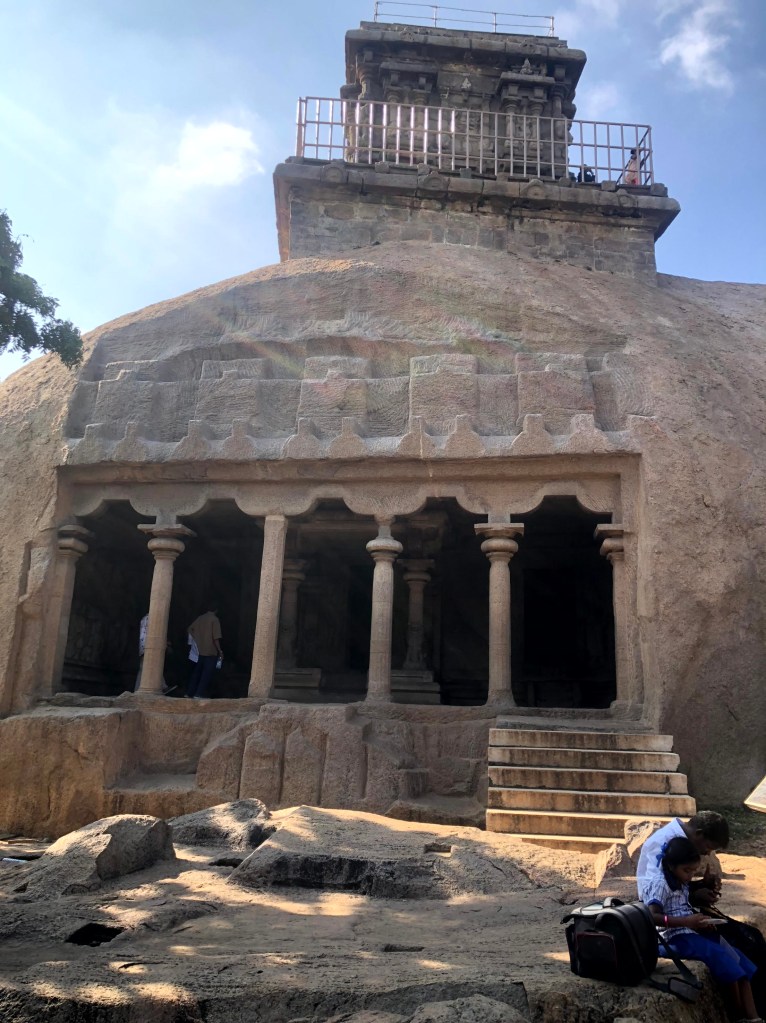

The massive, coarse pillars are in stark contrast to the later refined pillars of the Pallavas; hence on the basis of evolution, Mahendravarman’s cave temples stand as the earliest efforts of temple building in hard material. Inferring from the content of the inscription which alludes to the novelty of such an attempt; scholars like K.R Srinivasan even claim that this was the first cave temple sanctioned by Mahendravarman.

The use of stylistic features to assign structures to a particular patron or in a chronological sequence becomes more understandable when observed that similar features are found in cave temples located at considerable distances. Almost at a distance of 96km from Mandagapattu (Villianur district), is a place called Mamandur on the way to Kanchipuram where there are a set of 4 cave temples (two unfinished). While two (unfinished) southern caves are attributed to the successors of Mahendravarman, the finished northern ones are attributed to Mahendravarman based on two criterias. Stylistic features stand out as the prime criterion.

It’s hard to not notice the similarity of these cave temples especially the pillars; despite the fact that they are located almost ninety six kilometres apart ! The Cave-1 in Mamandur has Mahendravarman’s inscription whereas, adjacent Cave-2 has no inscription of the Pallava period and is attributed to Mahendravarman solely based on stylistic features and its vicinity to Cave-1. Interestingly, Cave-2 has two Chola inscriptions and one of them mention “Rudravalishvaram“, while the other one mentions “Valishvaram“, suggesting that it was a temple dedicated to the worship of Lord Shiva. One can also discern the traces of painting on these caves, allowing the observer to imagine the splendor and grandeur of these temples when they were first consecrated.

The ‘Mahendra style‘ of temples (a term coined by art historians), with such features can also be found in Dalvanur, Tiruchirapalli, Pallavaram, Vallam and Siyamangalam. These stylistic features gradually give way to the ‘Mamalla style‘ prominently found in the cave temples and rathas in Mahabalipuram. While the ‘Mahendra style‘ pillars, as can be seen, were divided into three parts; the top and the bottom cubical sadurams and the middle octagonal kattu; the ‘Mamalla style‘ pillars were more slender and had a squatting lion in the bottom. These pillars also had a sophisticated capital unlike the ‘Mahendra style‘.

The ‘Mamalla style‘ is not just attributed to Narasimhavarman (held the title, ‘Mahamalla’ ~Great Wrestler or Great Warrior), who was Mahendravarman’s son and successor; in fact there is no way the structures in Mahabalipuram (except the Shore Temple) can be ascribed to one ruler. Hence it is accepted that they were sanctioned during the latter part of the reign of Narasimhavarman and his grandson Parameshvaravarman.

One of the most exquisite pieces of art, generally believed to have been sanctioned by the ‘Mamalla‘ himself is the Varaha cave temple. It does not just mark the refined phase of cave architecture in succession to the cruder Mahendra structures; the interiors of the temples also have panels of Gajalakshmi, Trivikrama and Varaha (the boar incarnation of Lord Vishnu) carved with marvelous finesse.

Another beautiful cave temple of the ‘Mamalla style‘ is the Mahishamardhini cave temple known for its two beautiful panels, ‘Sheshashayana Vishnu’ and ‘Durga as Mahishamardhini‘. The Mahishamardhini panel is magnificent in terms of its scale, detailing and carving of images in motion.

While cave temples are regarded as the earliest phase of Pallava structural experimentation; conventionally, it is believed by art historians that the intermediate stage was that of monolithic rathas; the Panchapandava rathas being the most prominent ones. These rathas also belong to the Mamalla period; but they stand out due their variety and the extensive debate stimulated among art historians on their utility and authorship. Not all of these monolithic structures were used for worship and most importantly they were also left incomplete. It is believed that these rathas were models (in stone) of various designs, perhaps earlier executed by the Pallavas in perishable materials. While the Draupadi ratha with its simple thatched, single cell design may throw light on the earliest forms of temple architecture, the other rathas like Dharmaraja, Arjuna and Bhima appear as blueprints for the later Dravidian style of temple architecture which developed in South India.

The nomenclature of these monoliths as ‘rathas‘ and its association with the Pandavas is a much later feature and there is no contemporary evidence to even remotely support it. Apparently, the name of Mamalla was misunderstood as referring to the Pandavas; the heroes of the epic Mahabharata.

The rock cut experimentation of the Pallavas finally gave way to massive complete structural temples during the reign of Narasimhavarman-2- ‘Rajasimha’ who was the son of Parameshvaravarman-1. Ideally what started with the pioneering efforts of the enterprising ‘Vichitrachitta‘ (Curious minded) Mahendravarman, saw fructification during the reign of his fourth generation descendant. Rajasimha is credited for constructing the Shore Temple in Mahabalipuram, Talagirishvara Temple in Panamalai, Kailashanatha Temple and Vaikuntha Perumal Temple in Kanchipuram.

These temples marked the pinnacle of Pallava architecture; deserving special mention are Kailashanatha and Vaikuntha Perumal temples in Kanchipuram. The Kailashanatha temple is a marvel in itself; the compound wall/enclosure also called the prakara of the temple, houses rows of cells numbering 58 (as recorded by the ASI; Prof. Padma Kaimal claims it to be 64).

Dr. Padma Kaimal, Batza Professor of Art and Art History at Colgate University has brought about interesting perspectives on the art in Kailashanatha temple. Though theoretically a temple dedicated to Lord Shiva, Kaimal has argued that the outer prakara (compound) with its cells is dedicated to the Goddess; similar to the Chausath Yogini temple in Khajuraho and other places in the central India, which appeared a few centuries later. The prakara embodying the female principle is seen as the yoni (vagina) which embraces the linga (phallus) in heterosexual intercourse; metaphorically dissolving the separate identities of the sexes; dualism. This has been proved by taking into account the various forms of the depiction of Goddesses in the temple; both in aggressive, martial form and in demure forms creating an equal balance between the Gods and the Goddesses.

Over a period of perhaps a hundred years, Pallava architecture in imperishable medium saw a transformation from the crude massive pillars of ‘Mahendra‘ to the highly ornate, sophisticated and complete Kailashanatha and Shore Temples; the construction of latter, especially the vimanas, undoubtedly involved the application of geometry and mathematical calculations.

However this narrative of the evolution of Pallava architecture propounded by art historians over the decades has not been without challenges. R. Nagaswamy argued that all the temples in Mahabalipuram must be ascribed only to Rajasimha; while another group of scholars like Marilyn Hirsh ascribe the authorship of the structures to Mahendravarman. While both these propositions challenge the ‘traditional evolutionary’ theory initially proposed by scholars like Jouveau Dubreuil and A.H Longhurst (later accepted by most historians); these revisionist theories can also be subject to questions, which hardly give satisfactory answers. If these revisionist theories are to be accepted, the question of ‘gaps’ become crucial; if the temples of Mahabalipuram are ascribed to Rajasimha, why was there a gap in building activity from the death of Mahendravarman to the rise of his great-great grandson Rajasimha; and the same question follows, if the Mahabalipuram structures are ascribed to Mahendravarman. In terms of their war with the Chalukyas, the immediate successor of Mahendravarman only saw success; moreover Chalukyan attempts from the earliest of times were more of punitive raids and display of dominance rather than deliberate attempts of conquest; this is testified by the pace at which the Pallavas recovered their territories after the invasion during the time of Mahendravarman. Moreover various difficulties like securing line of communication, the presence of other set of kingdoms down south precluded any Chalukyan intention of conquest. While such campaigns definitely must have burdened the economy; there is hardly any reason to say that building activity must have been stopped due to involvement in warfare. Such raids were parallel and coherent with the royal ideology, which along with the building of structural temples legitimized the royalty. Such raids had been common in the geographical setting of the Deccan and even in the far south; the Sangam age was never devoid of raids by chieftains, which was eulogized in poems; despite the fact that such raids were detrimental to the economy as pointed out by the historian, Rajan Gurukkal. Concepts like digvijaya and vijagisu were central to the royal ideology and considering the new wave of urbanization which had set in during the late 6th-7th century CE, which in fact had stimulated new forms ideology and legitimation, it is hard to imply a complete stalling of building activity due to warfare. In fact after Narasimhavarman’s capture of Vatapi (Chalukyan capital), Pulakeshi-2’s son Vikramaditya-1 recovered all the territory lost to the Pallavas, corresponding to the reign of Parameshvaravaman-1; and this would have been a very protracted affair. The variety and the detailed analysis of Pallava art and architecture points to contribution by successive kings starting from Mahendravarman to Rajasimha; especially because construction took a longer time, due to the use of hard medium. However this is not to deny the connection between the declining authority of empire/kingdoms and decline in architectural patronage; but instances such as this just point out to the complexities associated. Nevertheless the arguments put forward by these scholars in their works (mentioned in the references) are definitely worth a read.

A more intriguing question to ask would be the reason for this sudden shift to building in imperishable mediums like stone instead of the earlier used ‘brick, timber, metal and mortar’. While there are credible reasons to explain this shift; Marilyn Hirsh emphasizes on the personality of the pioneer Mahendravarman, who initiated this shift. Mahendravarman was indeed an enigmatic personality; certainly one of a kind considering the nature of inscriptions and other sources left behind by him. The manner in which the Mandagapattu inscription has been written and signed by him as ‘Vichitrachitta‘, a biruda or a title which essentially means (curious minded or ‘myriad minded’) bears testimony to his intellect and humor. The titles, which he gave himself where often pun intended characterized by the usage of ‘double entendre’. This becomes more clear in his birudas like ‘Mattavilasa‘ (drunk with pleasure) and ‘Branta’ with the suffix ‘akari’ which meant ‘the madman or the one out of his senses caused this to be made’ (Hirsh, 1987). Mahendravarman also wrote two plays, Mattavilasa Prahasana and Bhagavadajjuka; their contents only justifying his incredible personality and humor. Another title of his refers to his interest in paintings (‘chitrakarapuli’ which meant, the ‘Lion of Painters’); his knowledge in music is testified specifically by the Mamandur Cave-1 inscription.

Such birudas, some even ridiculing or making joke of himself; reflecting his superior intellectual and most importantly enterprising, progressive and daring outlook have been taken by some scholars such as Marilyn Hirsh to be one of the crucial reasons for the experimentation of structures in stone. Mahendrvarman has to be credited for using stone as a medium in the Tamil country where people where only used to seeing/using it for burials or memorials (megaliths). For such people Mahendravarman would indeed have been a Vichitrachitta or Branta ! It has to be noted that cave temples in the subcontinent or south of Vindhyas as a whole was not pioneered by Mahendravarman; the caves of Ellora, Ajanta, Karle, Bhaja Bedsa, Pitalkora, Guntupalli were carved many centuries before Mahendravarman’s attempt. In fact Pallavas’ Andhra roots are much acknowledged by historians through the early inscriptions. The Pallavas even had a provincial capital at Dhanyakataka (Amarawati/ Dharanikota); the Buddhist Stupa at Amarawati and other architectural edifices in the Andhra region would have definitely inspired Mahendravarman’s enterprises. While the pioneering efforts of Mahendravarman are not to be dissuaded, ascribing an individual solely, for such historic shifts would also be inappropriate.

Manu. V. Devadevan argues that from the period of Mahendravarman, there was a marked shift from the ‘cult of chivalry’ to the ‘cult of personality’. While the inscriptions of Mahendravarman’s predecessors were concerned with presenting the king as an ideal, chivalric person, strictly conforming to dharma; starting from the former, were impressive titles(birudas) praising the king’s personality. Mahendrvarman’s double entendre birudas have already been mentioned; there were also others like ‘Satrumalla‘ (a warrior who overthrows his enemies), Narasimhavarman’s ‘Mamalla‘, Parameshvaravarman’s Ekamalla (sole warrior or wrestler) etc.

The king’s personality was further endorsed by the christening of temples and tanks after him and his birudas. Mahendravarman’s cave temple in Dalavanur was named ‘Satrumalleshvaralaya’ (after his title Satrumalla), a cave temple dedicated to Vishnu in Mahendravadi was named ‘Mahendravishnugruha‘ ; a temple commissioned by Parameshvaravarman in Mahabalipuram was named ‘Atyantakama Pallaveshvaragruham‘ (though the biruda Atyantakama was also held by his son Rajasimha). In fact the Kailashanatha temple was originally called Rajasimheshvara or Rajasimheshvaragruham/Rajasimha Pallaveshvaragruham. Almost 100 titles of Rajasimha (over 300 as claimed by R. Nagaswamy) has been engraved on the prakara(compound) cells of temple (Stein, 2017).

Prof. Devadevan explains this transformation from the ‘cult of chivalry’ to ‘cult of personality’ as a result of the third wave of urbanization which had begun in the 6th-7th centuries, leading to the shift in emphasis from the ‘rural’ to the ‘urban’; characterized by the creation and cultivation of an ‘urban culture’ involving the construction of temples, use of Sanskrit and patronage to literature in classical Sanskrit, classical music and promotion of Agamic deities, themes and ideas. These themes have been effectively studied by scholars like Shonaleeka Kaul, Daud Ali and Sheldon Pollock.

These changes could not be brought about overnight and had to be cultivated over decades and centuries. The Somaskanda image is an excellent example of integration of local Sangam tinai deities into the mainstream Agamic pantheon. According to Prof. R. Champakalaksmi, Somaskanda was a Pallava innovation which involved Shiva along with Murugan and Korravai (Durga); the latter two being Sangam tinai deities (Lorenzen, 2008). While this image was first used by Parameshvaravarman, it was popularized by his son Rajasimha, during whose reign almost forty panels were commissioned (Lockwood, 1974).

Similarly the evolution of Pallava architecture bears testimony to the process and stages of cultivation of skills and taste in classical architecture; like the choice of material, the use of themes/iconography , craftmanship, the nature of pillars, pilasters; the pyramidal vimana etc. The pyramidal vimana which was finally executed on a massive scale by Rajasimha, shows a highly advanced knowledge of geometry and mathematical calculations!

The personality cult was not just endorsed through inscriptions and the naming of temples/tanks etc., they can also be observed in architecture; in the way kings sought to leave their ‘signatures’. Why is it that all the pillars in Mahendravarman’s cave temples situated kilometers away, had the same design? The same question can be asked for the pillars of the ‘Mamalla style‘, though these cave temples fortunately/unfortunately cannot be ascribed to an individual king! Similarly its hard to not notice the similarity in Rajasimha’s temples shown above, especially in the style of the vimanas/shikharas.

Notwithstanding the mentioned aspect, the different phases of Pallava architecture also show continuity and this is strikingly visible in Rajasimha’s Kailashanatha temple. The pillars in the front mandapa of the temple are of the ‘Mahendra style‘. Similarly, the prakara cells have ‘Mamalla style‘ pillars with lion base.

Emma Stein in her dissertation thesis makes an interesting observation on the choice of sites by Rajasimha for the temples. The Talagirshvara Temple is located in close vicinity to the Mandagapattu cave temple and Kailashantha is located close to the Mamandur cave temple(even though the Kailashanatha temple is located in Kanchipuram, the capital of the Pallavas; it finds itself in the western outskirts); throwing light on Rajasimha’s intention of establishing a ‘royal genealogy’; a continuity with his predecessors(ibid).

As mentioned in the introduction, ‘Art and Architecture’ enable us to map out certain aspects of history in a way, no other sources help. This was just a brief account of the ‘History of Pallava Art and Architecture’, history we can map out ‘from‘ Pallava Art and Architecture and also the history we can map out ‘from‘ the ‘History of Pallava Architecture’; inspired by the works of all those scholars who have worked on this for more than a century. What has come down to us is extremely valuable; we are duty bound, to acknowledge its value and make it more valuable.

REFERENCES

1.Lockwood, M., Siromoney, G., & Dayanandan, P. M. (1974). Mahabalipuram studies. CLS.

2. Longhurst, A. H. (1998). Pallava architecture. Director General, Archaeological Survey of India.

3.Lorenzen, D. N. (2008). Religious movements in South Asia: 600-1800. Oxford University Press.

4. Nākacāmi, I. (1969). The Kailasanatha Temple; a guide. State Dept. of Archaeology, Govt. of Tamilnadu.

5. Singh, U. (2019). A history of ancient and early medieval India: From the stone age to the 12th century. Pearson.

6. Srinivasan, K. (1964). Cave-temples of the pallavas. Archaeological Survey of India.

7. Devadevan, M. V. (2017). From the Cult of Chivalry to the Cult of Personality: The Seventh-century Transformation in Pallava Statecraft. Studies in History, 33(2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0257643017705195

8. Hirsh, M. (1987). Mahendravarman I Pallava: Artist and Patron of Māmallapuram. Artibus Asiae, 48(1/2), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.2307/3249854

9. Kaimal, P. (2005). Learning to See the Goddess Once Again: Male and Female in Balance at the Kailāsanāth Temple in Kāñcīpuram. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 73(1), 45–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4139877

10. Kalidos, R. (1984). Stone Cars and Rathamaṇḍapas. East and West, 34(1/3), 153–173. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29756682

11. Stein, E.N. (2017). All Streets Lead to Kanchipuram: Mapping Monumental Histories in Kanchipuram, ca. 8th – 12th centuries CE (Publication Number: 10633265)[ Doctoral Dissertation, Yale University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis Global.