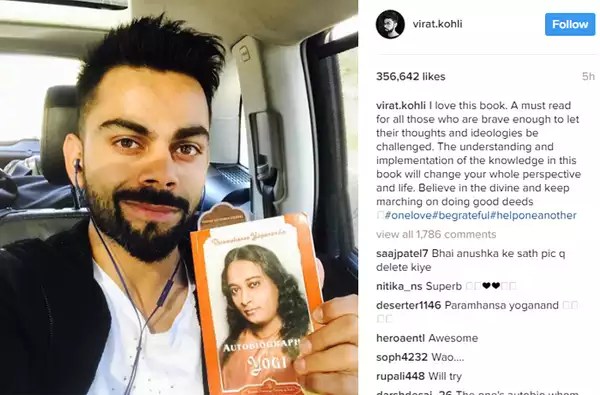

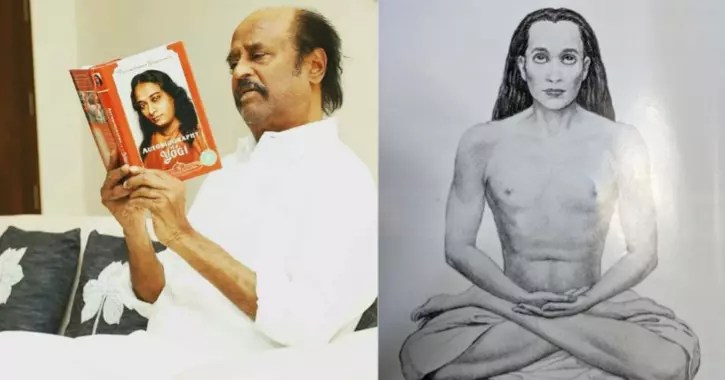

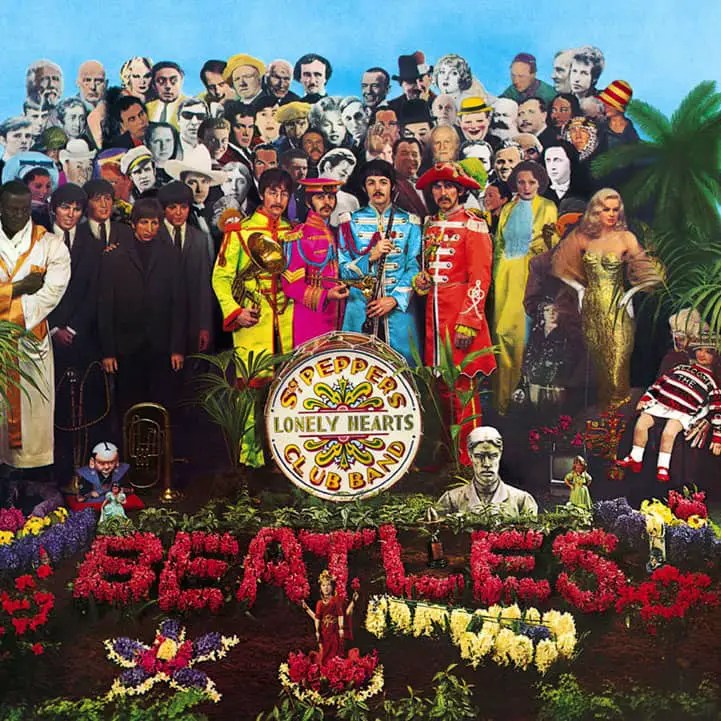

The widely popular, Autobiography of Yogi written by Paramahamsa Yogananda is a book, full of promise and possibility ! Considering its global appeal, with endorsements and testimonials from international celebrities across generations, pops up intriguing questions on the aspects of the book which appealed to people beyond cultures and nationalities? Was it the overarching spiritual message of Unity ? Unity with the Absolute, Unity of Humankind, Unity in the messages of Religious Texts; all of which are evinced in the book ?

While the appeal of spirituality across cultures and especially in the West is well known, the contents of the book is replete with a crucial element, whose impact on the reader could be profound, complex and nevertheless pronounced- the element of miracle. The book’s appeal to the spiritual tendencies of the reader is only complemented by this element

Mukunda Lal Ghosh was brought up in an elite Bengali Kayastha family and was one of the eight children of Bagabathi Charan Ghosh (employed in the Bengal Nagpur Railways) and Gyanprabha Devi. Young Mukunda’s sociocultural conditioning was quiet unlike the usual colonized bourgeois Indians, who sought to entrench/uplift their socio-economic status by clinging to colonial modernity. While it was common for the elite upper class/middle class Indians, to secure government jobs or a position of importance in the new economic milieu created by the British; the narrow class interests of the babus also proved to be a forerunner for the Indian National movement. A characteristic feature of the Indian, Western educated intelligentsia especially in the late 19th century, was their conscious acceptance of modernity and Western ideas even to the extent of harboring ridicule or contempt for non-Westernised downtrodden Indians. While the situation and beliefs held by the intelligentsia saw a gradual change by the turn of the century, characterized by strong scruples against blindly accepting the West; engagement with modernity and modern ideas formed a crucial (perhaps inevitable) component.

The book is both an autobiography of Paramahamsa Yoganananda and the biography of many saints and yogis who- as has been claimed- transcended the abilities of normal humans in varied aspects, and have either influenced his own personal quest or have proved as substantial examples of the possibilities in the way of life he expounded or lived.

For the young Mukunda, what fascinated/appealed to his imagination was not a Westernised/elite life of a government servant as would be the case among his relatives, family friends and wider social circle; but lives of saints and yogis often haloed with miracles. The miracles and enigmas often reached Mukunda by word of mouth, and the boy didn’t really content himself in blindly believing them but also made an effort to witness them. A crucial characteristic trait was his unflinching devotion and belief in the Divine. From early childhood, owing to Mukunda’s passionate faith in Divine, he did not just witness miracles as a third party observer, but also in his own life, in myriad ways ! Like the lives of many other young saints -as the monastic traditions of ancient-medieval India suggest- who left homes and renounced family ties at a young age, Mukunda’s quest for the Divine and most importantly a guru (teacher) in a modern setting is lucidly presented.

His experiences with his teacher (guru), Sri Yukteshwar Giri, undoubtedly stands out as the most significant trope in the book, irrespective of the chapters dedicated exclusively. The reason is fairly direct; justifiably venerated and celebrated in most Indian monastic traditions, the teacher-student or guru-shishya relationship forms the main conduit for continuation and spread of knowledge. The young adolescent who leaves his home, renouncing familial ties is completely under the responsibility of the guru who takes care of his sustenance, nurturing and education (not necessarily as we understand it in the modern sense !). In the process, there is an also an efflorescence of a relationship based on love and affection. The guru inevitably has maximum influence on the young monk; Sri Yukteshwar’s influence on Yogananda throughout the book and his lifetime is discernible.

Written from a Vedantic/Upanishadic worldview; the world of Yogananda and his gurus evinces tremendous possibilities. We have gurus and Yogananda himself reading minds of people, displaying tremendous psychic abilities; yogis appearing in different bodies, foreseeing the future, discerning the karmas of their disciples (or themselves), defying time and space, living without food for their entire lives, bringing people back from the claws of death, telepathic messages, having things completely go their way, tapping the knowledge of past and future lives and what not ! But all of this is not presented abstractly or out of the blue; and this is where Yogananda’s skill and ability as a masterful narrator deserves special credit.

The language is a neat blend of simplicity and sophistication, the tone- enthralling, and the larger meta narrative- through which all these miracles and enigmas get intelligible- Vedanta. Though a complex philosophy with sub-branches, Yogananda’s narrative avoids the complexities and attempts to deliver the larger message in a much simpler and experiential way. Nevertheless it also stands in conformity with the Yogic ethic which considers intellectual/philosophical exegesis and debate of scriptures, futile! The postulates of Upanishads becomes a matter of living experience rather than an intellectual exercise.

However Yogananda does not shy away from explanations, even attempting scientific explanations to the superhuman feats. Boldly citing even Einstein’s theories ! While a student of theoretical physics is always welcome to critically analyze the claims and pose counter-questions to Yogananda’s scientific understanding; the explanations to various phenomena assumes a tone and clarity capable of convincing the readers, especially the ones seeking a sort of spiritual validation. A marked feature aiding such explanations is the extensive use of footnotes which appear in almost every page- where complex Sanskrit terminologies or concepts are explained, additional/interesting information of the people mentioned, general information as regards to History/contemporary events, quotations from world literature and not to forget– ‘the most important’ and recurring footnote references- from the Holy Bible.

To substantiate his metaphysical worldviews, Yogananda generously uses quotations from the New Testament implying an ever affirming conviction that the underlying messages of the scriptures in both religions are essentially the same. Interestingly his guru, Sri Yukteshwar even wrote a book, The Holy Science specifically dealing with the parallels between Upanishads and New Testament. While the freedom to interpret Biblical texts independently and innovatively is more or less an accepted tradition dating back to the Reformation; the merit of such interpretations and their theological/metaphysical underpinnings are for expert theologians and academics of Christian theology to ascertain and judge. Nevertheless, Paramahamsa, who in his entire life – as can be discerned in the autobiography- acted with considerable conviction and clarity, had no qualms accepting the divinity of Christ and the abilities of enlightened Christian mystics. His persistent desire to meet the German mystic and Stygmatist Therese Neumann and his experiences validating her visions are noteworthy.

Apart from spiritual dimensions, it is also interesting to discern the history of times in which Yogananda lived, through his writings. The East-West, modernity-tradition debate unsurprisingly makes its presence, like it does in the writings of many novelists, writers, philosophers and social reformers of those times who have written about religion and society. Similar to Swami Vivekananda’s views, Yogananda believed that both East and West could borrow from each other; undoubtedly, spirituality was what the West could borrow and the East – ‘practical grasp of affairs’.1 While there is immense reverence and also a perceived superiority of Indian religious tradition and History; Yogananda’s message is of brotherhood beyond nationalities. His sojourn to the West was a vision of his gurus, who perceived the desperation for spirituality in the ‘materially’ inclined West which was leading itself (along with the world) to destruction. In the snippets of information provided on History- wherever deemed necessary-a clear influence of ‘nationalist historiography’ is visible for fairly valid reasons2; surprisingly there’s hardly any tinge of condemnation or disapproval of the British. He even recounts how he was approached by young men to lead a revolutionary movement during World War-1- he declined claiming that nothing good will come out of kiling ‘our English brothers‘3. Despite the influence of nationalist historiography, Yogananada- who spoke very little about Muslims- has only positive things to say about them4, even mentioning that both lived ‘side by side in amity‘ and that the partition was ‘a sad division‘, whose causes were ‘economic factors‘5. However his views can –in no way – be taken as representing that of the entire Indian population, or even the majority- such generalizations lining on idealism, only defiles the complexity of History. Like Tagore and perhaps even Gandhi, Yogananda’s deep rooted spiritual influences could be the reason for such views- despite the fact that they (especially Gandhi, if not Tagore and Yogananda) are vehemently blamed by fundamentalists to this day for the ‘idealism’ rooted in concepts like brotherhood and Universalism6.

Yogananda’s spiritual message embodies a syncretism not just with respect to other religions; but within Indian metaphysical traditions. His experiences of Union (with the Absolute )are not just on the lines of non-theistic monism (or Advaita) as is usually the case for yogis; Yogananda also has visions of Krishna, Kali, his dead master Yukteshwar and even Jesus ! The experience of communion promised in the scientific meditation technique of Kriya Yoga (which is closely connected to breathe), does not discourage Yogananda from engaging in fervent devotion or bhakti !

How do we understand this sheer diversity in approaching the Absolute ?

Syncretism in present day has acquired loaded meanings with political overtones- often used as an ammo against fundamentalist narratives. The usage of the word in this context seeks to steer clear of such baggage. Undoubtedly Yogananda’s ways7 come under what we understand as mysticism and spirituality; in variance with the ‘conformist’ based sects/religion. It must be emphasized that we are not talking in terms of binaries; religious beliefs and mysticism/spirituality are not necessarily conflicting/contradicting entities. Yogananda’s principle obsession is the communion with God- the Absolute, which is an experience, a living reality; and like most traditions of mysticism, it (directly or indirectly) rebukes the fetish with outward garbs like identity, scriptures, rituals, philosophical/intellectual debates etc., as the real sojourn is inward, through meditative silence . The myriad ways he witnesses communion appears as a message for seekers to not waste time arguing about the means, for, in the end, there is no debate !

Yogananda succeeds in taking the reader to a totally different and lesser known world; where sorrow and misery are marginal, where there is hardly any space for vices; a world without hustle, identity crises and insecurities; totally unimaginable in the modern world of the 20th century and perhaps even today. While the book can be a treat for believers/theists, spiritual seekers (sadhakas) and undoubtedly the ‘avowed’, ‘passionate’ believers and inheritors of Indian religious and cultural tradition…..

…how are non-believers, atheists, agnostics and people with rational/scientific outlooks expected to engage with such narratives ?

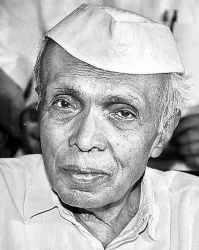

This becomes imperative as the book is replete with miracles and we live in a world -which for legitimate reasons- does not believe in such phenomena. That Yogananda’s claims and experiences may appear to be sham for skeptics and rationalists (despite his effort to explain the law behind it) is a very strong possibility. Modern India has seen no less ‘Godmen’. The very term may evoke a sense of disdain because of the complicated experiences modern Indians have had with gurus (and so-called gurus). Along with allegations and acquittals in cases like rape, physical harassments, money laundering; other aspects like the otherworldly pretensions, and most importantly miracles have made modern-day gurus, both a figure of ‘cultic’, ‘messianic’ veneration and contempt. It also gave rise to Rationalist Movements and Associations, led by scientific minded rationalists, who passionately went around disproving the miracles (putting it under the banner of ‘superstition’) and the abilities to perform them. H. Narasimhaiah, Abraham T Kovoor, Basava Premanand are just a few names representing such attempts; which even targeted the renowned Puttaparthi Sathya Sai Baba.

It ultimately becomes a showdown between science vs ‘belief/superstition‘ and people are put in tougher spots than is usually imagined. The dilemma spills on to a lot of aspects in every day life. Many a times, people find it difficult to engage with spiritual discourses of gurus because of these dilemmas, prejudices and stereotypes .

So what is the way forward ?

One can always play the card of choice; and leave it open to the readers whether they want to believe or not. Belief – not just in the miracles, but the entire approach, spiritual quest as a whole ! That may hinder us from going deeper. But the question even for the believers, is whether ‘belief’ is the right –or only -approach ? Are we to totally let go of the scientific temperament bequeathed to us by humankind over the course of last few centuries? Or, does it mean that rationality must only be selectively applied and the course of religion and spirituality is better tread by keeping aside rationality ? Are science and spirituality, binary opposites like it is perceived for tradition vs modernity/ science vs belief ?

Unlike popular perception, ‘Spiritual quest’ does not necessarily have its basis on belief. In fact belief may not be the best trait for a spiritual seeker.

According to the famous (and infamous) mystic OSHO Rajneesh, the spiritual quest is to know, not believe; when one ‘knows’ the need to believe doesn’t exist. This is were notional binary opposites of ‘spirituality vs rationality‘ takes a back foot and spirituality stands on the shoulders of rationality. Here, it also becomes imperative to broadly distinguish between philosophy and spirituality. What philosophy postulates , spiritual mysticism experiences. Absolute Monism/Neo Platonism /Non Dualism/ Advaita, Dvaita are philosophies no doubt ! But so are they experiences, living realities for spiritual mystics. Yoga is not just a set of exercises for weight loss, cholesterol, fitness, diabetes etc., but practical ways to facilitate and witness Union. While there is ground for debate in philosophy (not just with other, but ourselves), for a ‘Truth Realized’ mystic, there is no debate; there is just the experience of Truth8. The Truth/Absolute Reality if we may understand broadly, is the ultimate answer of the quest. The nature of Truth or sat, whether it is in concurrence with Monism/Non-Dualism is subjective; but only for the one who hasn’t realized it; its objective for the one who has witnessed it. Might seem like a wordplay, but even in the contemporary world where we are dealing with ‘Posts’ (Post Modernism, Post Structuralism, Post Colonialim) ideas like ‘objectivity’ and ‘truth’ are problematized.

While spiritual traditions exhibit a wide range of diversity, the need to let go of beliefs forms a crucial component according to views of the world renowned spiritual figure Jiddu Krishnamurti. Jiddu, whose essential argument is about ‘choice less awareness’ calls for abandoning all pre-existing beliefs, religious ideas, theological/philosophical knowledge (an umbrella term called ‘conditioning’ is used) as pre-requisite for such a quest. So does the (mostly misunderstood) mystic OSHO Rajneesh, who denounces all holy scriptures and the idea of believing.

But what is this quest, all about ? Why pursue it, after all ? What is at root of this quest ?

Historian Manu .V Devadevan in his widely acclaimed book, A Prehistory of Hinduism, attempting to understand what religion really accounted in premodern India, traces its underlying preoccupations to suffering. While the English terms, ‘religion’ and ‘spirituality’ have Eurocentric connotations and their semantic parallels in the context of Indian languages is another discourse.9 For the sake of convenience and a broad understanding, we may understand that the roots of spiritual quest lie in the inescapable reality of suffering. The four noble truths of Buddha, acknowledges it as the key aspect.

It is not just physical suffering, but mainly the mental suffering at the root of which is desire( scholars further specify ‘carnal’ desire). We are not just talking about suffering in ‘extremes’, but of varying degrees; even the daily conflicts we face within ourselves; the moments of frustration, pleasure, love, attachment, sadness, gloominess, jealousy, anger, hatred, selfishness, lust which may not be as deep rooted/pronounced as we would like to believe. Desire in its multi varied forms, in varying degrees pushes humans into the ocean of suffering. It is this desire owing to which peace and happiness always eludes wo(man); bouts of happiness never last, there is no feeling of fulfillment and the cycle of joy and sorrow continues.

Connected to desire, is the human thought. The common saying goes, ‘An idle mind is a devil’s workshop‘. Is there ever a moment where there is no thought running in the mind ? Its rather not surprising, if one totally does not have control over thoughts; which keep flowing, connecting in unimaginable ways; if meditatively observed, a marvel in itself !

Where do these thoughts come from?

An excerpt from the remarkable work, “The Book of Mirdad” by Lebanese poet, novelist and philosopher Mikhail Na’ima, answers this flawlessly,

“By merely thinking ‘I’ you cause a sea of thoughts to heave with in your heads. That sea is the creation of your ‘I’ and which is at once the thinker and the thought. If you have thoughts that sting, or stab, or claw, know that the ‘I’ in you alone endowed them with sting and tusk and claw.“

Thoughts and Desire rise from ‘I’ or ‘Self’ perceived by us; and many spiritual traditions consider this Dualism, where we perceive ‘I’/Self existing as a separate entity, to be a mere illusion; and the quest is to realize that ‘I’ which is the Absolute. Now to think about it, how often do we use ‘I’ and the pronouns associated with it like- my effort, my hard work, my wife, my girlfriend, my fame, my respect, my land. The claim to possession presupposes an ‘I’ which claims as ‘its’. J. Krishnamurti analyzes this with stupendous clarity10. He says, what we have is an image of ‘I’ (or rather I is just an image). The ‘I’ we hold on to, is nothing but an image accumulated by all past impressions, experiences, cultural conditioning. An image which is constantly changing ! It is this image which is hindering any perception in totality. When we feel hurt, betrayed, cheated or angry it is the image we claim as ‘I’ which is getting affected. We have created images of ourselves and others; hardly able to see anything or anyone the way it is/way they are, without a pre-existing image. The image of ‘I’, which is the creator of a ‘sea of thoughts‘ -ultimately a bunch of accumulated impressions from the past- is constantly changing as we accumulate more impressions; hence there is state of constant fear and the inability to stay in the present without any thoughts. Thoughts after all, are either coming from the past (as we perceived them) or are imaginations of the future, which is again strongly rooted in the past impressions. So perhaps most of us are living in the past, which is technically dead ! Again quoting from the Book of Mirdad,

“By merely feeling I you tap a well of feelings in your hearts. That well is the creation of your I which is at once the feeler and the felt. If there be briars in your hearts, know that the I in you alone has rooted them therein. Mirdad would have you know as well that that which can so readily root in, the same can as readily root out.“

In a state of no thoughts there is no ‘Self’; a state of Sunya. It is broadly on these lines that ‘Union’ must be understood. Yogic tradition claims that, this is a ‘state’ of tremendous possibility. Whether the possibility is of performing miracles or whatever ! What is possible at that state should not be the concern !

A seeker’s journey is about dwelling on these questions, in a meditative journey of Self inquiry. That, ‘I am not the Body, I am not the mind’, is no diktat to live by, but a living realization; not just another thought which flashes in the mind. The Self-Inquiry entails ceaseless questioning. Upanishads, which critically deal with such aspects is composed as a dialectic between a teacher and student; the latter being totally uncompromising in his pursuit. The ethic of rational/scientific questioning is not necessarily in deviance with spirituality. In fact ceaseless inquiry by shedding all form of pre-existing notions (conditioning), even if it is forgoing all traditionally accumulated knowledge, maybe the path.

This is not to belittle or trivialize the other approaches or the diversity in the historical and contemporary approaches to the Absolute (Inclusive of subjectivities). That there exists paths, rooted in belief and faith, cannot be denied. But so does the ‘rational path’ !

Spirituality is no virtue, whose possession is going to endow the so-called seeker with the right to moral policing; nor is it something, by the inclination of which one can perceive oneself as being on a higher ground than the other. There is no need of spirituality if one is able to engage in life without conflict (inner). If one can keep a steady mind, see things the way they are, there is no need for any spirituality, religion or God. The quest, is inarguably for the ones who want to ask deeper questions and not brush them aside as philosophy11. For those who have experienced suffering, and observe that no matter how intelligent or how good their intellect, stops giving answers or gives answers hardly satisfying or assuaging. Maybe in a different context, but one is reminded of the protagonist Raskolnikov in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, when he says

“Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth.“

Acknowledging the degrees of subjectivity in the given statement- of the author and the protagonist in the context of the story- and with no intention of creating a division between ‘intelligent and less intelligent men’; the statement beautifully betrays that intelligence may help in understanding sorrow, but not necessarily mitigating it. Spirituality is just for the ones who ask (or want to ask) deeper questions; who observe the conflicts within them and try to find its roots rather than distract themselves. It is a choice !

To conclude, it doesn’t matter if one would like to believe in the miracles or any of otherworldly tendencies mentioned in the book. The miracles are not a lure; it is blatantly futile if one seeks to engage in the quest, just to be able to perform/witness such feats. They are merely a promise of possibilities. It is for the reader to decide whether such a promise should be the spark behind the spiritual quest. Beyond the world of miracles, the autobiography is a passionate, loving call for a quest to perceive and engage in pursuing the Absolute. A quest which does not divide people into religion, creed, race, faith, nationalities etc., but that which perceives Oneness and brotherhood- not just in theory, but as a living reality !

NOTES

- pp.466 ↩︎

- ‘Valid reasons’ because nationalist historiography apart from the drawbacks which we can point out on hindsight, was the most acceptable narrative in contrast to the earlier narratives on Indian history written from the ideals of Utilitarianism. There is no inherent assumption that because Yogananda was ‘Hindu’ he subscribed to a Hindu Nationalist narrative, as ‘Nationalist Historiography’ is accused of (rather hollowly !) ↩︎

- pp.468 ↩︎

- Italaicized for emphasis- The community based religious identity owes a lot to colonial/modern perceptions. Identities existed in pre-modern India and the difference in faith also was also expressed through identities, but not such totalizing ones as Hindu-Muslim ↩︎

- pp.468 ↩︎

- Tagore was known for critique of nationalism and propounding Universalism ↩︎

- Italicized as I am slightly skeptical of using the term creed/belief or any other ↩︎

- The word Truth has been used in a very broad context, signifying the experience when the quest is fulfilled. On the other hand, from a scholarly/academic perspective Manu.V . Devadevan in his Pre-History of Hinduism has claimed that concepts like ‘Transcendental Truths’ are mostly Semitic in origin and sat never really had a constant meaning in Indian metaphysical traditions.. ↩︎

- Read Chapter-1, Indumauli’s Grief and the Making of Religious Identities, in the above mentioned book, for a detailed discussion ↩︎

- Read, Freedom from Known and other works of J. Krishnamurti ↩︎

- In disdainful sense, like its used in common parlance ↩︎