Schools of historiography have constantly laid out guidelines for the writing of history in tandem with the ideologies prevalent in the respective periods. Their propositions have not just been a broad framework for writers, but also the suggested approach for readers. Nevertheless, there’s no way to control how history is perceived or interpreted by individuals. The insights a reader draws from history are never bound by any guidelines and can never be !

In a country like India, history acts as a mystical trump card used as a response and an assuaging medicine against all hardships. This isn’t just restricted to the literate section of the population. Temples all around the country have interesting myths about their provenance; which definitely cannot be defined as history, but is perceived so, by the people. Myth and history are indeed different but not entirely incongruous. Ultimately it’s the perception that matters. While conversing with a rural dweller about a local temple; one can often get to hear about the local legend of the deity and a striking point in most of the cases is that, they connect the antiquity of the temple with divinity. When they say that a temple is ‘very very old’, it is mostly accompanied with a feeling of divinity and mysticism.

This is not just restricted to the illiterate section of the society. Ever since mind blowing discoveries about Sanskrit were made in the 18th century; and the rich evidence of a continuous, whooping 5000 year history of the subcontinent mapped out in the following centuries; the literate Indians have left no stone unturned to perceive their superiority over the Europeans. Early 20th century Indian historians and readers; the wounded civilization held on strongly to the rich evidences about their provenance, boosting their armaments in the struggle for self rule.

Thinking about it, there’s nothing wrong in taking pride about a rich history; just like every aspect of development and advancement in the world is ascribed to ‘Enlightenment’ which took birth in Europe. The narrative today is that, all developments starting from Industrial Revolution, democracy, representative governments, communism, capitalism had its origin in ‘Enlightened’ Europe. The same narrative is used to even justify colonialism; the existing level of development and democracy in the Third World countries is only because the seeds of Enlightenment were sowed through colonialism. While this is a totally different debate; the point being, when Europe and the West can take pride about being the “generous benefactors” of Enlightenment; why shouldn’t we take pride about the level of philosophical advancement reached as early as the first millennium BCE. American Transcendentalism pioneered by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; German Romanticism drew influences from the Upanishads !

Likewise, a very important episode in ancient India often evokes a sense of suspense, mystery and curiosity among us Indians, who knowingly or unknowingly seek to take pride in the superiority of our past; Alexander’s campaign of India. The events ended in such a suspense and disappointment because it was just short of a culminating encounter of Alexander and the Magadhan army.

What would have happened if Alexander’s army hadn’t mutinied ? Could Alexander have defeated the long standing army of the Nandas or Chandragupta who usurped the throne; the following year ?

An answer to these questions would have provided a fitting response to the excitement and reviving confidence of the wounded civilization. Unfortunately historians and readers had to satisfy with the “what if” propositions, which indeed weren’t disappointing; favorable as a matter of fact. Though the encounter of Porus and Alexander in the banks of river Jhelum, ended in the defeat of the former; readers could take pride in the fact that his army fought gallantly; considerably damaging the vigor of the Macedonian army. The famous legend about the conversation between Alexander and Porus after the war didn’t blemish the dignity of Indian readers either; further strengthened it !

After the battle of Hydapses, when Alexander sought to advance to the Ganges; his army resisted and expressed their disapproval; if not mutinied. After deliberation, Alexander finally agreed to return back home; by first sailing down the Indus to the sea and from there to Babylon. However, even if it meant a retreat, arrangements had to be made. The whole purpose of the campaign undertaken would be futile if he would not make the necessary arrangements for administration, governance of the conquered territories etc., in order to consolidate his empire; for it to be more than a mere raid !

Hence, all the small tribes on his way back were either destroyed by his army or themselves surrendered. On his way down river Jhelum, Alexander realized that two tribes were ready to resist his passage; the Mallians and Oxydracians (identified as Kshudrakas). The Mallian campaign undertaken by Alexander is an interesting one. As usual, Alexander’s master planning and military strategy led to a massive defeat of the Mallians, who were also a formidable fighting tribe. Yet the campaign ended with a dramatic turn of events.

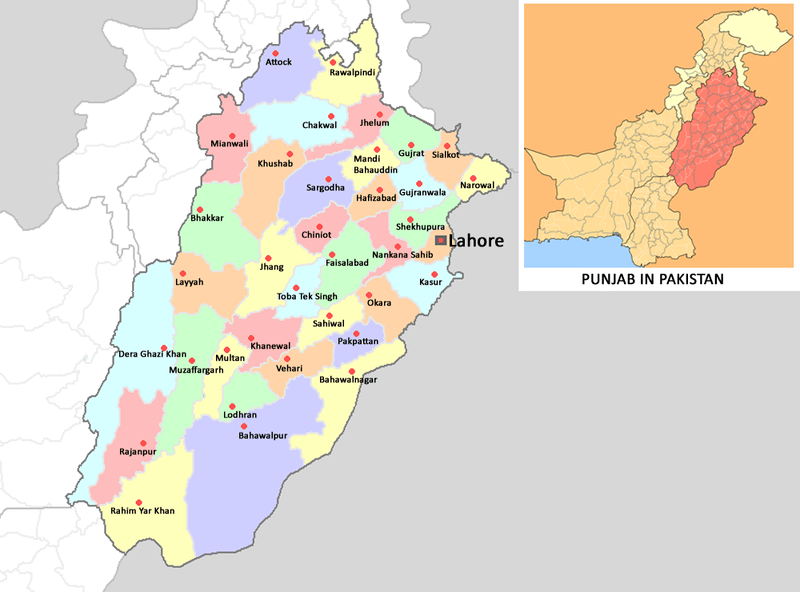

The Mallian state was in between the Chenab and Ravi rivers; also comprising the region around present day Multan in the Punjab province of Pakistan. While Alexander’s contingent marched and sailed down the Jhelum river; the confluence of Jhelum and Chenab marked the beginning of the campaign. The land between the two rivers (Chenab and Ravi) was a desert and one of the Mallian capitals Agallasa (present day Kamalia, Toba Tek Singh district), was across this desert.

Alexander divided his army and sent them in different directions, so as to ensure that Mallians would not get a chance to escape. He sent one contingent down the right bank of Chenab, another following the same route through the river; a third one was sent along the left bank of Chenab. The former had to secure the region where Ravi joins Chenab to make sure the Mallians do not get any reinforcements; the contingent on the left bank was to stop the evading Mallians before they reach the former contingent. Alexander, then again divided his army such that he would first march across the desert with a few troops and another troop was to follow three marches behind him to kill the Mallians who would escape upstream.

The alliance between Mallians and Oxydracians broke at an earlier stage, although they were expecting Alexander’s army. The Macedonians’ success lay at the beginning stage of planning itself; Alexander had decided to march across the desert and attack Agallasa; a move least expected by Mallians. An army with its cavalry, infantry forces marching across a dessert would have been hard to imagine for anyone, let alone the Mallians!

When Alexander reached the city of Agallasa, the inhabitants were taken by surprise and were completely unprepared; roaming outside the city walls. The city walls were easily reduced and the inhabitants fled to defend themselves from the citadel, where they fought gallantly. Following this, the inhabitants fled from one city to another and the events unfolded in the same pattern; the city wall reduced easily and a tough defense at the citadel. The Mallian cities of Harapa (Sahiwal district), Tulambo and Atari (Khanewal district) were reduced. The escaping Mallians, wherever spotted were killed; in fact Alexander had even sent his troops in different directions to ensure that they have no place to escape.

The final task was to then siege the largest capital city of the Mallians, present day Multan. The inhabitants had fled even before Alexander reached and had positioned themselves upstream Ravi, on the western side. A brief encounter of armies ensued followed by the same pattern; where in, the Mallians secured themselves inside the citadel and offered resistance.

It has to be noted that the Mallians defended each of their citadels gallantly; even setting their own wooden structures on fire and hurling it on the intruders. Sieges generally lasted for hours.

Unable to break the defense, Alexander became restless and ordered for ladders. When ladders were arranged, he immediately started climbing before anyone could. Climbing with a sword and shield, he reached the top; his soldiers and bodyguards panicked as their leader ventured defenseless and alone into the enemy territory; crowding around the ladder, trying to climb. Three others reached the top, when the ladder broke. Alexander who was hanging on the rampart refused to jump back even at the request of his soldiers. He jumped straight into the citadel, immediately being attacked and surrounded by Mallians with his back against the wall. He killed a few including their leader; but in no time, he was surrounded by Mallians shooting arrows. One arrow struck his helmet and another struck his chest; Alexander fainted. Meanwhile the soldiers who had jumped and the others who had reached through ladders, human ladders, pegs etc., shielded the injured Alexander and took him to the tent.

The arrow was three fingers thick and four fingers long. The arrow head had penetrated into the lungs and wooden shaft had to be chopped off. Alexander did recover after a few days, but the troops were completely distraught. Rumors had spread that their king was no more. Only when the injured Alexander boarded the vessel to wave at his troops stationed in the banks of Chenab; would they believe that their savior was still alive !

The Mallians however, finally submitted. But this again urges the reader to ponder over the alternatives. Macedonians may have had defeated the Mallians, but would have lost their leader who led them all the way from Greece. They would have even retained the territories conquered, governed them etc., but Alexander, would have been remembered in history as being killed during his last battle with Mallians; the overall outcome going unnoticed.

Plutarch who later documented Alexander’s campaigns, mentioned (after claiming to have read Alexander’s letters) that the battle with Porus had “taken the edge off Macedonians’ courage”, compelling them to return back, as further progress meant facing even more formidable and larger armies.

Even if analyzed in terms of military skills, the Indians were no less than their Greek counterparts; when in 305 BCE, Selucus Nicator (a former General under Alexander) sought to invade, the Mauryan army under Chandragupta Maurya inflicted a defeat.

The Indian archers were also really skilled and used bows which were up to six feet long. Greek historian Arrian claimed that nothing could resist the long Indian arrow which could penetrate the shield and breast plate together ! If an arrow head could penetrate deep into the lungs of a warrior like Alexander, even donning a breastplate; then this observation would definitely not have been an exaggeration.

The defeat of tribes on his way back to the sea created a power vacuum in the region of Punjab, making it easier for Chandragupta Maurya to include it in the vast empire he would take control of. Renowned historian Burton Stein even suggests the possibility of Chandragupta’s involvement in the disapproval expressed by Alexander’s soldiers !

Nevertheless, the arrow which struck Alexander is symbolic of the possibilities, suspense and the impact created by the Greek entry in the history of the subcontinent !

Historians even deduce that Mallians later migrated to the south/south east, occupied the region of central India; which got the name Malwa.

REFERENCES

- Dodge, T. (1890). Alexander. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Wheeler, B. (1902). Alexander the Great. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Keay, J. (2013) . India a history. [London]: HarperCollins.

- Thapar, R. and Spear, P., 1979. A history of India. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Stein, B. (2012). A History of India. New Delhi, New Delhi: Wiley India Pvt. Ltd

- Kosambi, D. D. (2016). An Introduction to the Study of Indian History. New Delhi, New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt.

- Banerji, A. (1931). THE MĀLAVAS. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 13(3/4), 218-229. Retrieved June 20, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41688247

- 2021. The ladder breaks stranding Alexander and a few companions, within the Mallian town. André Castaigne (1898-1899).. [image] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mallian_campaign#/media/File:The_ladder_breaks_stranding_Alexander_and_a_few_companions_within_the_Mallian_town_by_Andre_Castaigne_(1898-1899).jpg> [Accessed 20 June 2021].

- 2021. Pakistan Punjab. [image] Available at: <https://www.jatland.com/home/Jhang> [Accessed 20 June 2021].

- 2021. Location of Punjab in South Asia. [image] Available at: http://<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punjab> [Accessed 20 June 2021].

2 replies on “When the arrow struck Alexander….”

Wow! An extremely enriching article! Thank you very much for this

LikeLike

Thank you so much ❤️Really Grateful 🙂

LikeLike